A patent is a legal monopoly over the manufacture and sale of a unique, physical invention which you, the creator, have exclusive access to over a period of time.

A utility patent gets you legal protection of the function of a particular invention. These types of patents can cover the process, composition, or improvements to a product.

A patent can be used as both a shield and a sword to prevent others from using your invention as their own and also allows you to create or license your product.

We’ll help you secure this property so you have peace of mind knowing that no one else can profit from your idea.

In many ways, intellectual property such as patents may be thought of as common real property. Picture a deed to a house. What does it describe? One would imagine that the deed would describe the land boundaries and other characteristics describing the house such as its address. Now try to imagine a deed to invention. Trickier right?

From a policy perspective, a patent functions as a disclosure from the inventor to teach the public how to make and use an invention in exchange for the right to exclude others, for a certain amount of time, from making, using, selling, and importing the invention into the United States. A patent makes this disclosure through a specification; however, unlike the property deed, a patent lays out the “metes and bounds” that is the boundaries and characteristics of the property right vested in the inventor through the patent claims.

The constitutional framework for obtaining a patent can be found in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution which grants congress the power to “promote the progress of science and the useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” The United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) is the government agency that oversees the granting of patents. There are three types of patents: utility, design, and plant patents.

A utility patent protects the functional features of an invention. To obtain a utility patent, an inventor must file a patent application to be examined by the USPTO. When most people think of a patent application, they think of a non-provisional patent application. Generally speaking, a utility patent has a term of twenty (20) years.

The United States permits both provisional and non-provisional patent applications to protect the utilitarian aspects of an invention. A provisional patent application is a type of legal document filed in the USPTO that allows an inventor to establish a filing date for a period up to one year. The provisional patent application itself does not become an issued patent until the applicant files for a non-provisional application within one year of the filing of the provisional patent application. A provisional patent application will never become an issued patent and is not substantively examined by a examining patent attorney at the USPTO. However, a provisional patent application offers individuals and businesses several advantages. Provisional patent applications require lower USPTO filing fees and haw less legal requirements than their non-provisional patent applications so generally speaking provisional patent applications are less costly for a patent attorney to prepare.

When a provisional patent application is correctly filed with the USPTO, a product covered by the provisional patent application may be marked “patent pending.” Having an product covered by a provisional patent application marked “patent pending” may provide a marketing and competitive advantage. The provisional patent application provides a provisional right to exclude others from making and using the invention; thus, may act as a strong deterrent from competitors.

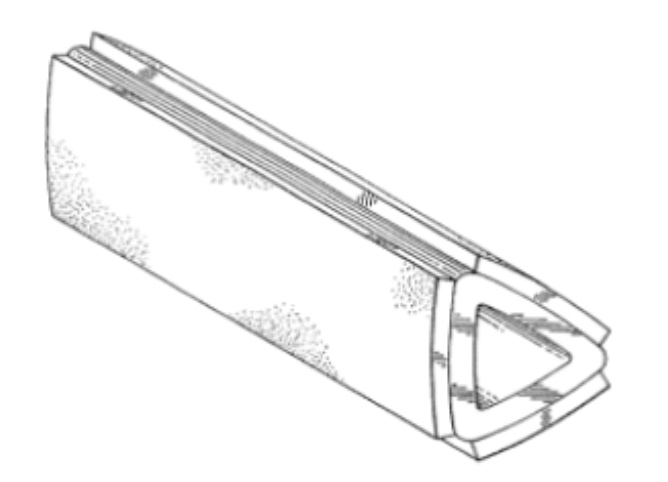

Entities use design patents to protect new, original and ornamental designs for their products. While functional designs are not patentable, designs that incorporate functional features may still be patentable if there are ornamental features that exist independent of the design’s functional aspects.

Unlike utility patents which have a term of twenty (20) years from their initial date of filing with the USPTO, design patents have a term of 14 years – 15 years. The most important component of a design patent are its drawings. Because design patents are simpler to draft and require less time to prosecute than a utility patent, design patents are typically less costly to obtain.

Another unique quirk regarding design patents on a products’ design or packaging is that when the term of a design patent expires, in certain cases, the owner of the design patent may still seek protection of the design through trade dress protection for as long as the patentee continues to use the design.

Design patents cover only the elements illustrated as solid lines. Dotted lines denote elements of the design that are not covered by the design patent. The fewer solid lines a design patent has, then the broader the property rights may be.

Plant patents are granted by the United States government to inventors who have invented or discovered and asexually reproduced distinct and new varieties of plant. Plant patents blur the line of patent eligible subject matter to protect living plant organisms with unique sets of characteristics determined by its genome and only replicated through asexual reproduction and cannot be otherwise “manufactured” and have a duration of 20 years from their date of initial filing with the USPTO.

WHAT IS A PATENT SEARCH/PRIOR ART SEARCH?

A patent search, also known as a prior art search is a search for documents that could affect an applicant’s ability to acquire patent rights on a particular invention. In the patent world, the term “prior art” means disclosures or documents such as scientific publications, patent registrations and patent applications that are known to the public before a patent application is filed. In many cases, inventors and small businesses in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area will have a prior art search conducted before developing an invention.

Generally speaking, after an applicant files a patent application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), an Examining Attorney at the USPTO will perform a prior art search to determine what prior art exists that might affect the patentability of the invention. This is also the case for every other country in the world.

Under United States patent law, to be patentable an invention must be patentable subject matter, useful, new, and non-obvious. For a more detailed explanation of these requirements please review the article “Can I Patent My Invention?”. However, for the purposes of this article, suffice it to say that if the USPTO Examining Attorney finds a single prior art disclosure, or is able to combine multiple prior art disclosures that disclose all elements of the invention seeking to be patented, then the Examining Attorney may reject the invention as un-patentable in what is known as an Office Action.

While not legally necessary, many applicants and inventors will have a patent attorney conduct a prior art search and analyze the results of the search before filing or deciding to file a patent application. This is because the patenting process has significant fees and costs associated with it and in many cases, it may take years for a patent application to complete the examination process. Because of this, many individuals and businesses in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area will have a prior art search conducted so that a patent attorney can determine the probability that an invention will be granted a patent before deciding to draft, prepare and file a patent application. Analyzing the prior art before filing an application also assists an individual or business in deciding what type of patent application to file and offers support in crafting a strategy for protecting ideas and inventions. Businesses and inventors in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area use prior art searches and patentability opinions to decide how best to protect an invention and to make pragmatic business decisions.

In the United States, only patent attorneys licensed to practice before the USPTO can analyze the results of prior art searches and advise clients as to the probability of being able to patent an invention. The team at The Plus IP Firm is available to conduct prior art searches and to analyze the results. The team, including attorneys Derek Fahey and Mark Terry, has analyzed thousands of inventions, and advised numerous clients as to the probability of acquiring a patent on their invention. The attorneys at The Plus IP Firm have also assisted clients in acquiring numerous patents in a variety of areas, including software patents, mechanical patents, electrical patents, and chemical composition patents.

Should you have any questions regarding patents, filing patent applications or prior art searches, then contact the attorneys at The Plus IP Firm for a free consultation.

As a patent attorney exclusively practicing intellectual property law, one of the questions I am often asked at work and at cocktail parties alike is “can I patent my invention?” That question makes me smile every time. I love helping people develop and protect their inventions and creations. So, when I get asked, “can I patent my invention” or “is my invention patentable,” I know that the answer is “maybe.” That is because there are several types of patents and the answer depends on what the invention is and the inventive aspects of the idea or concept. For this article, I will focus on utility patent protection, which protects the functional features of an invention.

Whether you can patent an invention is different for each invention; however, the analysis used to determine whether an inventor can obtain a patent on an invention is fairly similar for every invention. Under United States Patent Law, for an invention to be patentable it must be new, useful, patentable subject matter and non-obvious. These four requirements are what Examining Patent Attorneys at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) use to determine if an invention is patentable.

New

For an invention to be new it must not be known or used by others before the inventor claims to have invented it. When a USPTO Examining Patent Attorney is analyzing a patent’s claims to determine if an invention is patentable, the Examiner searches various databases to find publications, patent applications, patent registrations and patent publications that disclose elements of the invention seeking to be patented. If the USPTO Examiner is able to find a single disclosure that discloses all elements of the invention as claimed in the patent application, then the USPTO Examiner will issue a rejection, known as an Office Action, claiming the invention is not new or novel. It is a patent attorney’s job to dispute the Examiner’s rejection and point out the differences between the invention and the disclosures cited by the Examiner.

Useful

For an invention to be useful it must be usable and provide some sort of benefit. This is an extremely low hurdle. In fact, the shelves of the patent office are filled with strange and bizarre patents such as a Kissing Shield, a Banana Protection Device and the Comb Over Patent a.k.a. Method For Concealing Partial Baldness. A patent application will very rarely get rejected because it is not useful.

Patentable Subject Matter

Patentable subject matter is defined as any machine, manufacture, process, composition of matter or any useful combination thereof. It may be easier to define patentable subject matter by what is not patentable subject matter. Laws of nature, physical phenomena, abstract ideas, and logic are not patentable subject matter. For instance, gravity and the first law of thermodynamics, which are laws of nature, cannot be patented. One of the types of inventions that USPTO Examiners typically reject for not being patentable subject matter is software related inventions. That is not to say that software is never patentable. In fact, the team at The Plus IP Firm prepares, files and obtains patents for software inventions on a frequent basis. However, a software patent application must be crafted in such a way that it consists of patentable subject matter under the law. The law regarding patentable subject matter for software related inventions is constantly changing and as such, you should seek the help of a registered patent attorney to assist in drafting an application to ensure that you have the greatest probability of overcoming any such rejection.

Non-obvious

The most common obstacle to the patentability of an invention is the non-obvious requirement. The non-obvious requirement is that the invention cannot be obvious to a person with average skill in the knowledge area of the invention. USPTO Examining Patent Attorneys can combine multiple disclosures or references to argue that an invention should not be patented. For example, let us say you were trying to patent a black toy car. Let us also say that the USPTO Examiner did a prior art search and found a disclosure revealing a blue toy car, along with another disclosure revealing a black truck. The Examiner could combine the blue toy car disclosure with the black truck disclosure and argue that it would have been obvious to invent a black toy car, and therefore, the black toy car would not be patentable. As mentioned above, it is the job of the patent attorney to dispute the Examiner’s rejection and point out the differences between the invention and the disclosures cited by the Examiner.

Many times, I recommend to my clients that a patent search, also known as a prior art search, be conducted before filing a patent application. While not legally necessary, the purpose of a prior art search is to find existing patents, patent applications and other documents that could affect the patentability of an invention. The results from a patent search can be used by a registered patent attorney to determine the probability that an invention will be granted a patent. The results of the patent search are also helpful in creating a strategy for protecting ideas and inventions. Speaking with an experienced patent or intellectual property attorney will be helpful to understand how best to protect an idea, concept or innovation given the goals and budget of a business or inventor.

Having the right patent attorneys on your side to guide you through the application and registration process can make all the difference. You can learn more about Derek Fahey Esq., one of the patent attorneys at The Plus IP Firm by clicking HERE.

A patent search, also know as a prior art search is a search for documents that could affect an applicant’s ability to acquire patent rights on a particular invention. In the patent world, the term “prior art” means disclosures or documents such as scientific publications, patent registrations and patent applications that are known to the public before a patent application is filed. In many cases, inventors and small businesses in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area will have a prior art search conducted before developing an invention.

Generally speaking, after an applicant files a patent application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”), an Examining Attorney at the USPTO will perform a prior art search to determine what prior art exists that might affect the patentability of the invention. This is also the case for every other country in the world.

Under United States patent law, to be patentable an invention must be patentable subject matter, useful, new, and non-obvious. For a more detailed explanation of these requirements please review the article “Can I Patent My Invention?”. However, for the purposes of this article, suffice it to say that if the USPTO Examining Attorney finds a single prior art disclosure, or is able to combine multiple prior art disclosures that disclose all elements of the invention seeking to be patented, then the Examining Attorney may reject the invention as un-patentable in what is known as an Office Action.

While not legally necessary, many applicants and inventors will have a patent attorney conduct a prior art search and analyze the results of the search before filing or deciding to file a patent application. This is because the patenting process has significant fees and costs associated with it and in many cases, it may take years for a patent application to complete the examination process. Because of this, many individuals and businesses in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area will have a prior art search conducted so that a patent attorney can determine the probability that an invention will be granted a patent before deciding to draft, prepare and file a patent application. Analyzing the prior art before filing an application also assists an individual or business in deciding what type of patent application to file and offers support in crafting a strategy for protecting ideas and inventions. Businesses and inventors in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area use prior art searches and patentability opinions to decide how best to protect an invention and to make pragmatic busines decisions.

In the United States, only patent attorneys licensed to practice before the USPTO can analyze the results of prior art searches and advise clients as to the probability of being able to patent an invention. The team at The Plus IP Firm is available to conduct prior art searches and to analyze the results. The team, including attorneys Derek Fahey and Mark Terry, has analyzed thousands of inventions, and advised numerous clients as to the probability of acquiring a patent on their invention. The attorneys at The Plus IP Firm have also assisted clients in acquiring numerous patents in a variety of areas, including software patents, mechanical patents, electrical patents, and chemical composition patents.

Should you have any questions regarding patents, filing patent applications or prior art searches, then contact the attorneys at The Plus IP Firm for a free consultation.

Patent prosecution is the process of drafting, filing, and negotiating with the U.S. Patent and Trademark USPTO in order to obtain patent protection and rights for an invention. One must be a patent attorney or patent agent to prosecute a patent application on behalf on an individual or business with United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). At The Plus IP Firm, our attorneys and patent agents are registered to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office and have prosecuted hundreds of patent applications on behalf of clients throughout Florida, including businesses and individuals in the Tampa Bay area.

To best understand the patentability of a particular invention, a “patent search,” also known as a “prior art search” is typically completed before filing a patent application with the USPTO. A “prior art search” is a term used to describe a search to find patents, patent applications and other publications that may affect an applicant’s ability to acquire a patent on an invention. Although a “prior art search” is not legally required before an applicant files and begins to prosecute a patent application, many applicants choose to have such a prior art search conducted and have a registered patent attorney analyze the results to prepare a “patentability opinion.” A patentability opinion will typically include the probability of acquiring a utility patent on an invention. Many businesses and individuals in the Tampa Bay area and throughout Florida use the patent attorneys at The Plus IP Firm to prepare a patentability opinion to understand the ability to obtain a utility patent on an invention and other ways to protect an invention.

Office Actions

If a patent application does not meet either the statutory laws, or the USPTO rules and regulations, a USPTO Patent Examiner may issue either a rejection or an objection in the form of a document known as an Office Action. Applicants have a limited statutory amount of time to respond to an Office Action before a patent application will go abandoned for not responding to the Office Action. One of jobs of a patent attorney is to respond to the Office Action with legal arguments necessary to overcome a USPTO Patent Examiner’s rejection. Typically, a USPTO Examiner may issue a rejection based upon one of the following statutes:

35 U.S.C. § 101 Rejections: Requirement for Patent Eligible Subject Matter

An Examiner at the USPTO may reject a patent application based upon 35 U.S.C. § 101 (“§ 101 rejection”) stating that the invention is not “patentable subject matter.” Patent Attorneys at The Plus IP Firm are experienced in responding to these Office Actions and can assist you in overcoming such rejections. In fact, Mark Terry, Esq., one of the firm’s partners, is a former USPTO Examining Attorney. Mr. Terry uses his insight and experience obtained at the USPTO to assist his clients to overcome rejections based upon non-eligible patent subject matter. Additionally, Derek Fahey, Esq. frequently responds to 101 rejections for software related inventions for his clients.

35 U.S.C. § 102 Rejections: Requirement for Novelty

An Examiner at the USPTO may reject a patent application based upon 35 U.S.C. § 102 (“§ 102 rejection”). In a § 102 rejection, a USPTO Patent Examiner would argue that a single prior art reference was publicly disclosed or known before the filing date of an Applicant’s patent application, contains each and every element of the Applicant’s claimed invention, and therefore the claimed invention is not patentable. The patent attorneys at The Plus Firm are experienced in responding to § 102 rejections and are prepared to overcome § 102 rejections. Most often, a § 102 rejection is overcome by pointing out why the prior art cited by an Examining Attorney does not disclose all elements of the claimed invention or by amending the objected claims.

35 U.S.C. § 103 Rejections: Requirement for Non-Obviousness

An Examiner at the USPTO may reject a patent application based upon 35 U.S.C. § 103 (“§ 103 rejection”). In a § 103 rejection, a USPTO Patent Examiner would argue that multiple “prior art” references may combined in order to teach all elements of an Applicant’s claimed invention. An Applicant may have several routes to overcome a §103 rejection, including amending the claims to circumvent the § 103 rejection, arguing the combination of references was improper because it would render one of the references inoperable for the references intended purpose, and that the prior art “teaches away” from Applicant’s claimed invention.

The Patent Attorneys at The Plus IP Firm are passionate about helping inventors change the lives of others by helping inventors acquire and enforce their intellectual property and are prepared to zealously advocate by responding to the types of rejections listed above. If you receive an Office Action rejecting your patent application, then please call the patent attorneys at The Plus IP Firm to put your patent application in the best position to obtain a patent on your invention or to meet your business goals.

One way to view a provisional patent application is as a “place holder” in line at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). That said, a provisional patent application will not mature into an issued patent unless an applicant files a non-provisional patent application within one year of the provisional patent application filing date. There is no such thing as a “provisional patent.”

What is the difference between a non-provisional patent application versus a provisional patent application?

A non-provisional patent application will go through the examination process with a United States Patent and Trademark examining attorney, while on the contrary a provisional patent application is never examined.

Why file a provisional patent application?

Many businesses and inventors in the Tampa Bay area use provisional applications as a first step for protecting their inventions. A properly drafted provisional patent application provides a competitive advantage by establishing an early filing date for an invention. An early filing date is important under the United State patent law because, like every other country in the world, the United States now operates under a “first-to-file system.” A first-to-file system essentially means that the first applicant to file a patent application covering an invention has the rights to that invention.

A provisional patent application, when if drafted correctly, provides businesses and individual inventors with several advantages. Below are a few of the advantages of a provisional patent application.

Less Up-front Cost

One advantage of a provisional patent application is that a provisional patent application is typically less costly than a non-provisional application. A provisional patent application has less formal filing requirements than a non-provisional patent application. For instance, it may take the patent attorney less time to draft than a non-provisional patent application, and there are lower USPTO fees associated with it than a non-provisional application.

“Patent Pending” Status

Another advantage of a provisional patent application is that “patent pending” status is granted when a provisional patent is filed. Patent-pending status on an invention may provide an advertising and marketing benefit to an applicant. Additionally, a patent-pending status may ward off potential competitors from importing, making, selling, or using products covered by the provisional patent application. However,, businesses must keep in mind that, as mentioned above, a provisional patent application will never mature into an issued patent unless a non-provisional patent application is filed with the USPTO.

Time for Product Development

Another advantage of a provisional patent application is that a provisional patent application allows an applicant additional time to develop a concept further if necessary. Under United States patent law, after a non-provisional patent application (or the final examined application) is filed with the USPTO no new matter or content can be included in the non-provisional application. In many cases, while there is enough information available that would allow the applicant to adequately describe and explain the main element(s) of the invention, an inventor or business may need additional time to test and develop an invention. In these cases, a provisional patent application, if filed, would establish an early filing date for the main elements(s) of the invention, which allows the applicant to continue developing and improving the invention for up to one year at which time the applicant could file a non-provisional application disclosing all components of the invention. Many inventors and businesses in the Tampa Bay Area may use provisional patent applications as a way to continue developing their inventions while establishing an early filing date.

Formal Requirements – No Oath or Declaration Needed

Another advantage of a provisional patent application is that the USPTO does not require each inventor to submit an oath or declaration of inventorship. When a non-provisional patent application is filed by the USPTO, all inventors must submit and sign an oath or declaration of inventorship form, which may be difficult if inventors are unavailable or unwilling to sign the formal papers. Because the USPTO does not require a provisional patent application to be submitted with the formal filing

Extension of Patent Term

Yet another advantage is that the filing of a provisional patent application extends the term of the patent by up to one year. The term of a utility patent claiming priority to a provisional patent application, generally speaking, begins at the time the provisional patent application is filed and ends twenty (20) years after the filing date of the non-provisional patent application. The filing of a provisional patent application increases the patent term up to one year longer than if a provisional patent application was not filed before the non-provisional patent application.

Which type of utility patent application is right for me?

Depending on your business strategy, filing a provisional patent application may be the best option for your business. Many businesses and inventors in the Tampa Bay Area use provisional applications as an effective strategy for enhancing their intellectual property portfolio. The attorneys at The Plus IP Firm are available to assist you in determining if a provisional patent application suits your business and intellectual property goals.

Generally speaking, there are three main types of patents: utility, design, and plant patents. This article will focus on answers to questions that many Tampa Bay area businesses and inventors may have related to utility and design patents. A utility patent protects the functional features of an invention; whereas a design patent protects the non-functional features of an invention. In many cases a utility patent is generally the most sought-after patent because it provides protection for multiple embodiments. The owner of the utility patent has a right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling a patented invention within the United States or importing the patented invention into the United States. 35 U.S.C. § 271. These rights essentially give the owner a ‘monopoly’ over the patent invention for the term of the utility patent.

How long is my invention protected?

When an owner is awarded a utility patent, the duration of the patent, referred to as the ‘term of the patent’ or ‘patent term’ is 20 years from filing date of the non-provisional patent application in the United States. 35 U.S.C. § 154. The filing date is the date that the owner or applicant files the non-provisional patent application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). To learn about the differences between a non-provisional patent application and a provisional patent application, please reach out to us to our Tampa Bay patent attorneys to determine which type of patent application is right for you.

What is protected by a Utility Patent?

A utility patent protects the functional features of an invention. An invention may be a process, machine, and composition of matter or any improvements thereof. 35 U.S.C. §§ 100, 111. In other words, a utility patent may be granted for software inventions, electrical inventions, mechanical inventions, chemical inventions, and inventions involving a combination thereof. Our Attorney’s at the Plus IP Firm have experience with preparing, filing, and acquiring patents related to software inventions, mechanical inventions, electrical inventions, and chemical inventions. If you have an invention, we are available to discuss whether your invention is patentable and entitled to utility patent protection and the best course of action with regards to protecting your invention and business interests.

The most important aspect of a utility patent is the “claims” section. The claims describe what the applicant believes are the inventive and protectible features about the invention. The claims of a utility patent should be carefully crafted in order to provide the broadest protection available and protect your invention from infringers. Almost every word of the patent claims of a utility patent should be carefully selected to properly protect an invention. For example, the words “comprises” and “comprises of” have vastly different meanings when used in the claims of a utility patent. That is why it is crucial to hire experienced patent attorneys that know and understand the patent laws and USPTO rules when drafting a utility patent application.

What steps should I take to acquire a Utility Patent?

To begin the process of acquiring a utility patent, an applicant must file either a provisional patent application or a non-provisional patent application. There are benefits to both the provisional and non-provisional patent application depending on the current stage of development of your invention. Our patent attorneys at The Plus IP Firm are available to advise you as to what type of patent application(s) is best suited for your needs. To be awarded a utility patent, a non-provisional patent application must be filed. However, if a provisional application is best for the applicant’s current needs, then a provisional application may allow the applicant to have a 1-year grace period before filing a non-provisional application. As mentioned above, to learn about the differences between a non-provisional patent application and a provisional patent application, please reach out to us to determine which type of patent application is right for you.

After an applicant files a non-provisional utility patent application with the USPTO, an examining patent attorney at the USPTO then examines the non-provisional patent application to determine if it is entitled to patent protection under the current patent laws. If an examining patent attorney at the USPTO finds that a utility patent application is entitled to patent protection, then the examining attorney will issue the applicant a utility patent. However, if an examining patent attorney at the USPTO finds a utility patent application is not entitled to patent protection, then an examining patent attorney at the USPTO will send the applicant a document known as an “Office Action” explaining the reasons why the patent is not entitled to patent protection.

A patent attorney may respond to the Office Action with legal arguments carefully tailored towards the invention indicating why the applicant’s invention should be granted a utility patent under the law. The back-and-forth communication and legal arguments between a patent attorney and the USPTO’s examining attorney is known as patent prosecution. Our team here at The Plus IP Firm includes registered patent attorneys and patent agents experienced in prosecuting utility patent applications. Our team is available to assist businesses and inventors in the Tampa and St. Petersburg area to discuss concepts and inventions to determine if they may be entitled to utility patent protection.

Can you have multiple designs in a design patent?

Yes, it is possible that your design patent may include multiple designs or ‘embodiments.’ This possibility may save you both time and money when initially filing your design patent application. Although, you can only patent multiple designs in a design patent when the degree of variation between the embodiments is very small. The variation of features between the multiple embodiments must not be significant as to distinguish the distinct ornamental appearances of the overall design.

When are designs distinct?

Differences in the features of the embodiments may be considered insufficient to patentably distinguish when they are de minimis or obvious to a designer of ordinary skill in the art.

Designs are not distinct inventions if: (a) the multiple designs have overall appearances with basically the same design characteristics; and (b) the differences between the multiple designs are insufficient to patentably distinguish one design from the other.

Are there any specific requirements for the design patent application?

Yes, you must satisfy the enablement requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112. Therefore, the differences between the embodiments must be identified either in the figure descriptions or by way of a descriptive statement in the specification of the application as filed.

For example, the second embodiment of a cabinet discloses a single view showing only the difference in the front door of the cabinet of the first embodiment; the figure description should state that this view “is a second embodiment of Figure 1, with the only difference being the configuration of the door; it being understood that all other surfaces are the same as those of the first embodiment.” The obviousness standard under 35 U.S.C. §103 must be applied in determining whether multiple embodiments may be retained in a single application. See MPEP § 1504.03.

Will my design patent application get rejected if I include multiple embodiments?

A rejection is always possible for various reasons such as novelty, obviousness, non-patentable subject matter, enablement, and double patenting. If your design patent application has multiple embodiments, then the Examiner must determine if the embodiments are “patentably distinct” from one another. See MPEP § 1504.05. The term “patentably distinct” means that your application having multiple designs will be allowed only if they involve a single inventive concept. Two designs involve a single inventive concept when the two designs are patentably indistinct according to the standard of nonstatutory double patenting. See In re Rubinfield, 270 F.2d 391, 123 USPQ 210 (CCPA 1959). The degree of variation between the embodiments when determining whether they are patentably distinct will depend upon the Examiner’s discretion in deciding whether the inventions are distinct.

The Examiner must first determine whether the embodiments have overall appearances that are essentially the same as one another. If the appearance of the embodiments is considered to basically be the same, then it must be determined whether the differences are either minor between the embodiments and not a patentable distinction, or obvious to a designer of ordinary skill in view of the prior art. If embodiments meet both of the above criteria, they may be retained in a single application.

What happens if the Examiner finds a large degree of variation and independently distinct patentable designs?

If an Examiner finds a large degree of variation and independently distinct patentable designs, then the Examiner will issue a restriction requirement. The applicant would then be required to “choose” or elect one embodiment to be examined by the examiner. In response to the restriction requirement, an application could argue that embodiments are not patently distinct inventions. Alternatively, the applicant could elect one of the designs to be examined during the examination of the patent application. Additionally, an applicant could file a design patent continued prosecution application (CPA) to prosecute the remaining embodiments and to obtain the benefit of the filing date for the other designs.

The patent attorneys and team members at The Plus IP Firm have assisted clients in acquiring numerous design patents in a variety of areas and fields. If you have any questions regarding patents, filing design patent applications and design patent applications with multiple embodiments, then contact The Plus IP Firm.

Inventors and businesses seeking to create assets out of their innovations often ask, “What steps do I take after inventing a product?” While there is no single answer to that question, there are a few fundamental steps that most successful inventors take when developing an invention. The following steps will need to be accomplished if you intend to create a product or service out of your invention.

Step One: Conceptualize Your Invention in Writing

The first key step is to conceptualize, that is, to develop a concept and write your ideas on paper. This process will help to get your creative juices flowing. Draw a few figures to further help explain your invention. These drawings should capture what you believe is inventive about your invention. Additionally, the drawings will help your patent attorney analyze your idea. Those creating multiple inventions should take special note to keep all ideas in a notebook for safe keeping. Maintaining a notebook may also be useful in the future if you need to reference previous ideas.

Step Two: Perform a Prior Art Search

A prior art search is another critical step that should always be completed before you begin to develop your idea or invention. In patent jargon, the term “prior art” means documents, such as scientific publications, patents and patent applications that are in the public domain prior to the date you seek to file for a patent. A prior art search is a search for prior art is pertinent to your invention to determine if your idea has already been invented. Ultimately, a prior art search will help to determine the likelihood that you will be able to obtain a patent on a given invention.

Step Three: Conduct Market Research To Determine If Your Concept Makes Business Sense

If you aim to profit from an invention, then another critical step that you should consider is to conduct market research to help you determine whether there is a market for your invention. You should consider how many people would likely want to purchase your product if you were to sell it. Moreover, determine what percentage of those people have the means to purchase your product. Conducting preliminary market research will help you evaluate whether the money you might earn from selling your invention will be worth the time and resources that you will invest in developing your idea.

Step Four: Protect Your Invention

Yet another crucial step is to protect your invention by obtaining a patent on your invention. You might often hear the “Sharks” on the television sitcom “Sharktank”TM ask, “Do you have a patent on your invention?” A patent is a legal document that grants you the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing your invention into the United States. Obtaining a patent will provide you with a limited time monopoly, which ultimately will provide you with a huge competitive advantage. There are different types of patents that protect different aspects of an invention. For example, ornamental features on an invention are protected by design patents. On the other hand, functional features of an invention are protected by utility patents. An experienced patent attorney will help you determine the type of patent application most suitable for your needs.

Step Five: Have a Prototype Made

As a patent attorney, I am often asked, “Do I need a prototype in order to file a patent application?” The answer to that question is no – you do not need a working prototype to file a patent application. Many inventors acquire patents without having the means to reduce their concept to practice in order to produce a working prototype. However, once they have filed for a patent, many of those inventors will eventually enter into licensing agreements with others, who sell the invention and pay the inventor a royalty fee. Nonetheless, for those who intend to manufacture and sell their inventions themselves, a prototype can help you to evaluate and develop your invention. Recently, many of my clients have begun to use 3D printing for marking prototypes. 3D printing is a relatively new process for making a physical object from a three-dimensional digital model. 3D printing is much less expensive than making prototypes by traditional molding processes. Once you have a prototype made you can begin to test your invention to see what modifications are necessary. Additionally, a prototype may help you validate your invention.

Step Six: Validate Your Invention

Validating your invention is done by testing the performance of your invention through a series of trials. These trials may include having consumers test your product to determine if they are willing to use and purchase your invention. Validating inventions can be done by asking your family and friends to use your product, posting your product on social media, and measuring the positive responses, or, even stopping passersby on the street to try your product or invention. However, by publicly testing your invention you are placing it in the public domain, and you will have a short period to act before becoming prior art. Therefore, before doing this step you should strongly consider having your invention protected by filing, but at the very least, a provisional patent application to protect your invention from your competitors. Click here to learn more information about the benefits of a provisional patent application.

The attorneys at The Plus IP Firm have helped numerous businesses and inventors protect their ideas, concepts and creations with patents, trademarks, and copyrights. The attorneys at The Plus IP Firm have also helped businesses and inventors in many countries, as well as many regions in the United States protect their intellectual property. To discuss your options, click here to schedule a free telephone consultation with one of our experienced patent attorneys.

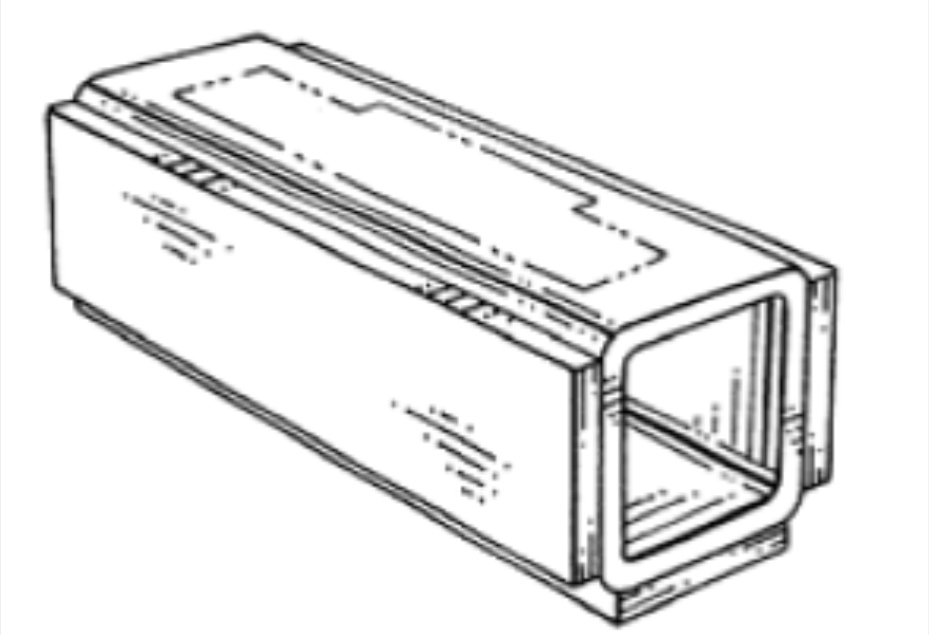

‘389 Patent

‘389 Patent Defendant’s Accused Buffer

Defendant’s Accused Buffer Nalico Buffer

Nalico Buffer Falley Buffer

Falley BufferA software patent protects a software program or an algorithm implemented on a computer. In the United States, software is patentable. If your invention is embedded in a software concept, like the Spotify app, it is a good idea to protect it via a software patent. Although a copyright can protect the actual source code, a copyright will not prevent others from developing the same software with the same functional aspects using different code.

In order for software to be patentable, it must be novel, useful and non-obvious with an identifiable improvement. It must also be tied to a machine. Additionally, software must be more than an “abstract idea,” meaning that the focus of the invention cannot simply be on a generic process, for which a computer is used simply as a tool to execute it.

The biggest challenge in obtaining a patent for software is fulfilling the usefulness requirement. In general, if the software innovation is highly technical, it is likely to be patentable. If your software uses a general-purpose computer to simply perform tasks that a person can do with a pen and paper, the software is probably not patentable. If your software, however, focuses on computing challenges and introduces a technical improvement to overcome those challenges (i.e., create new database structures, create new computations, improve computer speeds, reduce resources required, etc.) or performs a task in an unconventional way, then it is worth exploring the idea of obtaining software patent protection.

A great example is Microsoft’s database software using self-referential tables, which was deemed patent eligible since it improved the process of data storage and data retrieval in the computer. Airbnb has also patented its software system and method, which focuses on determining listings with the highest probability of being booked by the user. Doordash has a pending patent application for its automated vehicle for autonomous last-mile deliveries improving last-mile delivery of real-time, on-demand orders for perishable goods.

We always recommend starting with a patent search, in order to find out what inventions are already on the market and what parts of the software can be identified as novel. The patent search focuses on different perspectives, such as the end user’s view, the system’s view, and the computer’s view. Once the patent search is done, the results and the likelihood of obtaining patent protection are summarized in a detailed assessment report.

To find out if your software is eligible for patent protection, it is important to speak with a patent attorney who has experience with software related patents. Prior to meeting with your attorney, make sure you clearly understand which features of your software are most important from a business perspective and which ones were the most difficult to implement. Presenting these to your attorney, will allow him / her to determine if you should file a patent application. Contact us for a free consultation to get more details on the process and the costs involved.